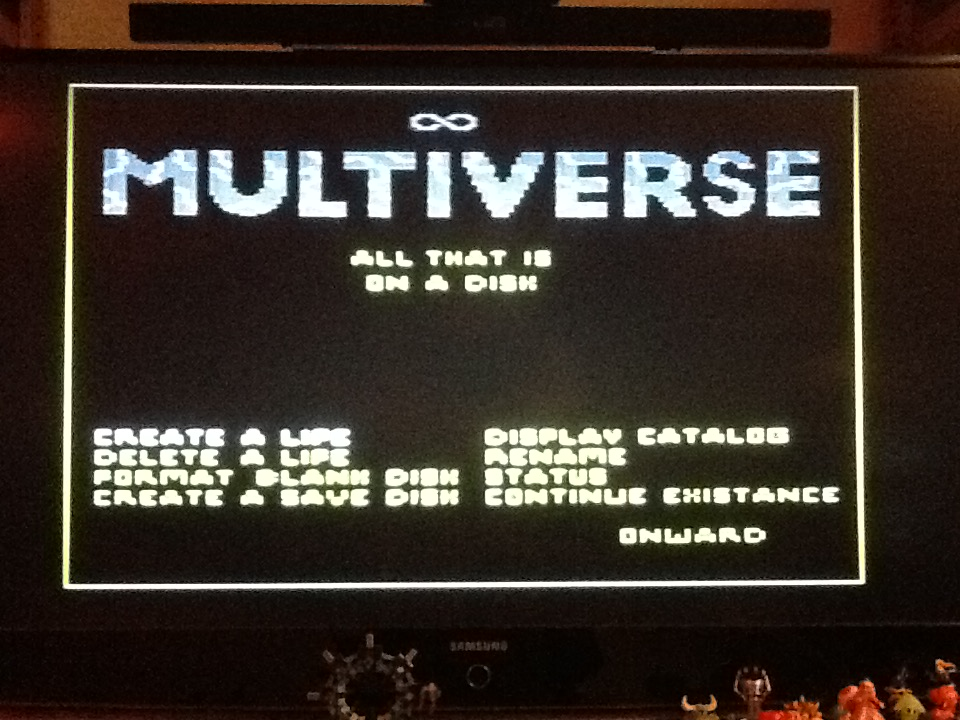

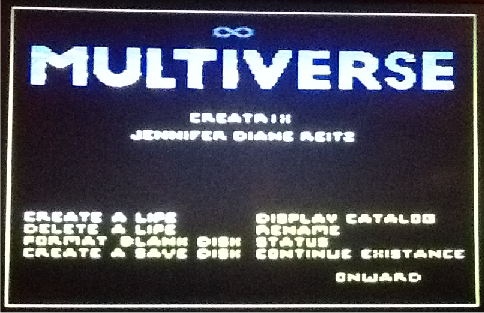

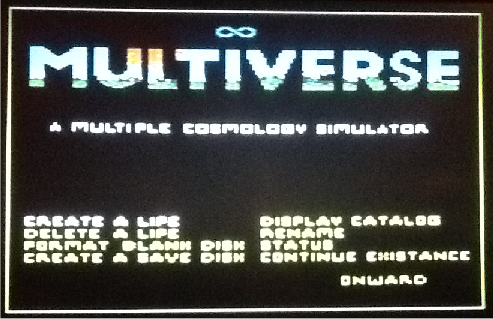

Multiverse Title Screen

The titles animated - the letters spelling Multiverse in marble fade to reveal animating scenes... landscapes, starfields, and other images:

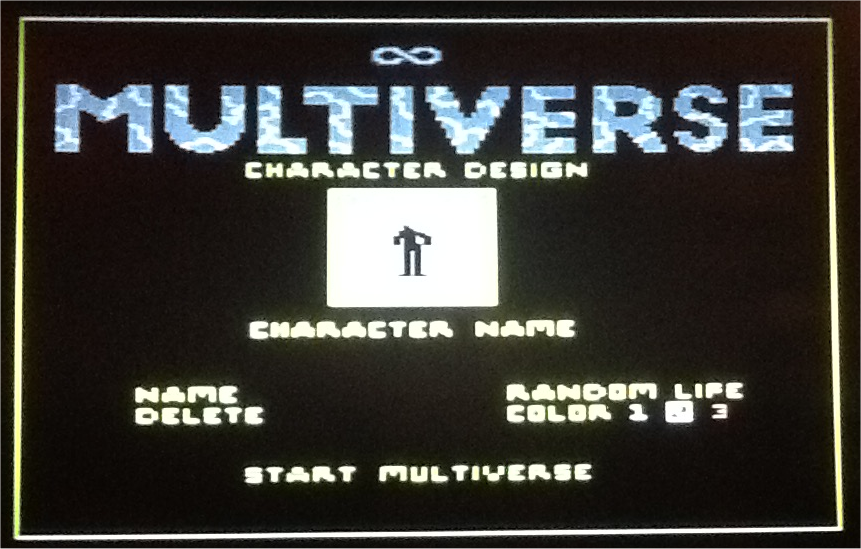

After that, we get the character creation screen:

Different bodies could be combined with different heads. You did not have

to be human.

Because of the limitations, color choices were limited, as

was the size of your character.

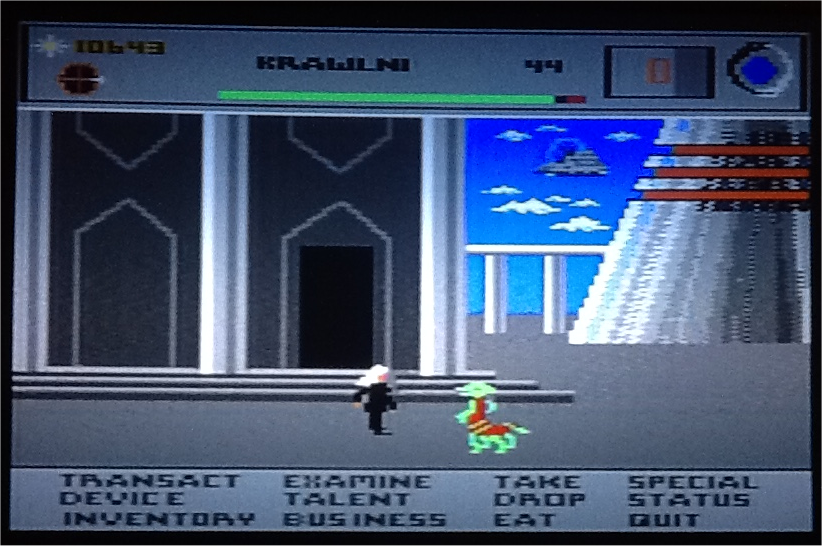

Players started on the hub-world of Krawlni. Kralni was a super-advanced

multicultural civilization that had mastered

multiversal travel. They

explored countless universes, each with unique physical laws.

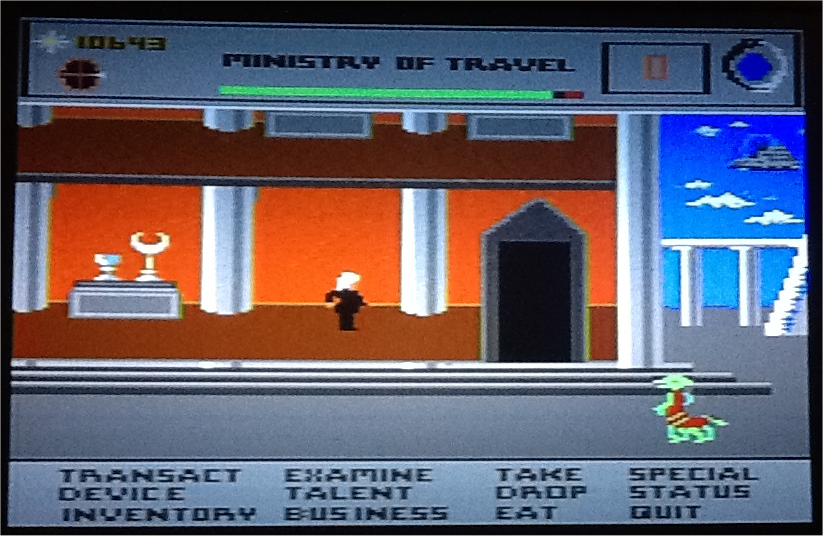

When you enter a building, the front fascade vanishes, revealing the

interior. Essentially there were only two

planes of movement. One for

landscapes, and one for interiors.

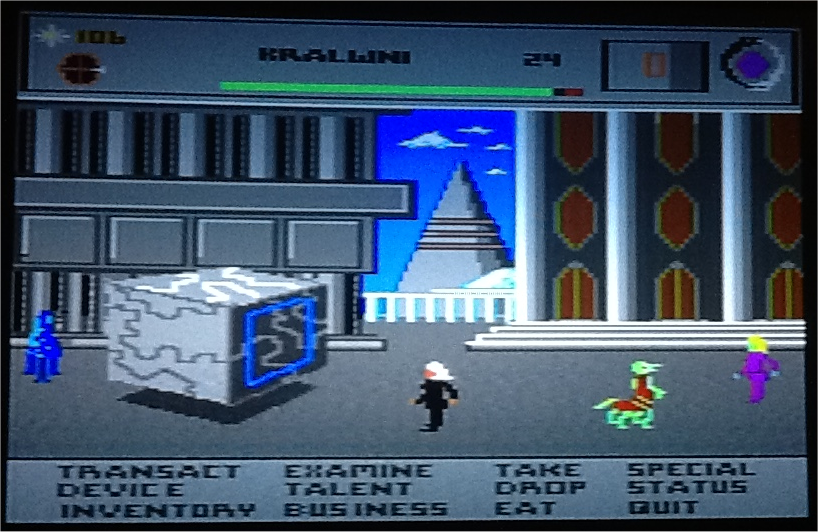

The cube is a Multiversal Mover. You enter through the side with the blue

square. Players could enter the buildings in Krawlni and

visit shops or

claim one of several apartment rooms available. The room acted as an

ultimate save point - if the player died, they would

always return to

their room on Krawlni (don't die!). It was a pain to get back to the

coordinates they had died in. You could also save

inside the Mover

whereever you were in the many universes.

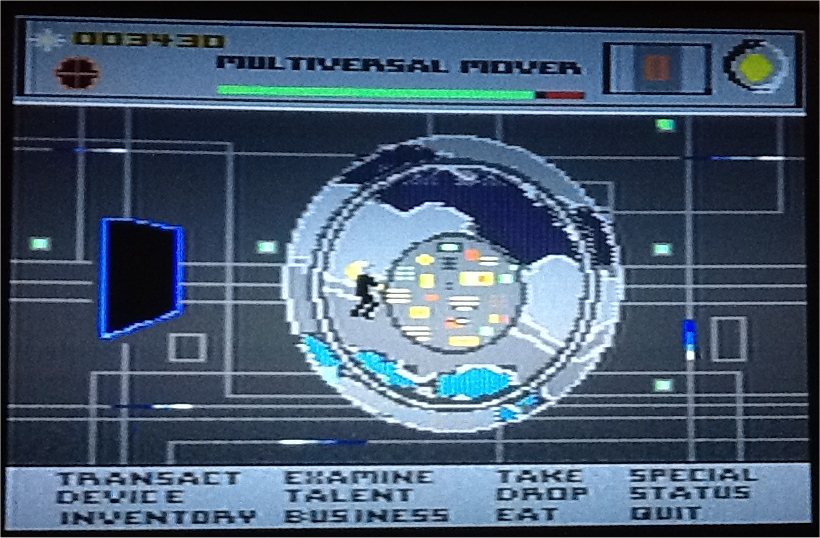

Inside, the Multiversal Mover was a free-scrolling representation of a

zero-G space, very high-tech.

The player could float around this space,

but the useful bit was the floating ball-shaped console in the middle.

that console is where one could access a screen to set coordinates for

multiversal travel.

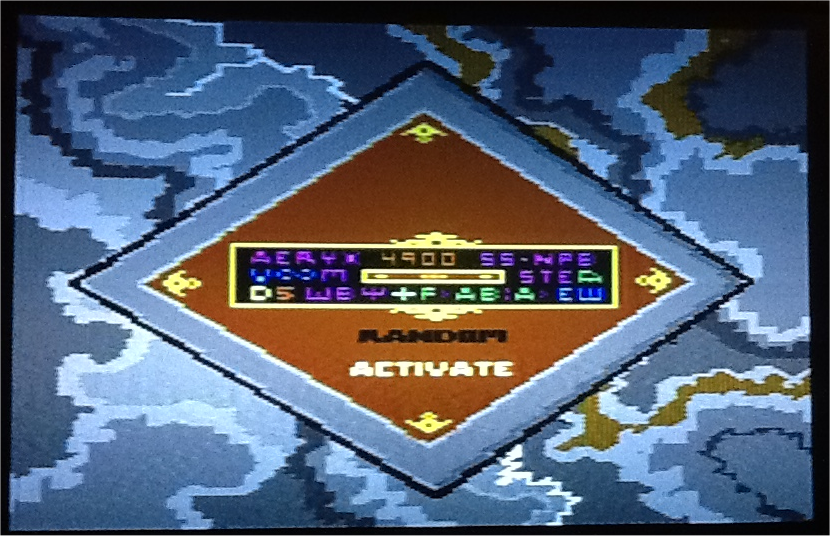

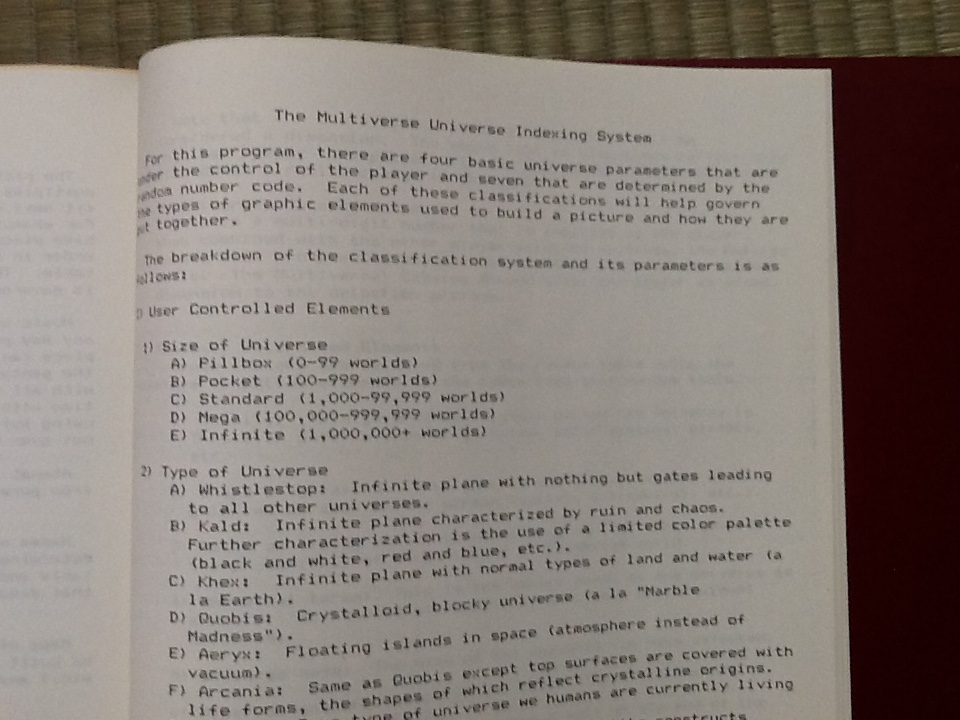

This is the control screen. By using the joystick, the various sections

could be altered to choose a specific

destination to travel to. The

first part was the type of universe, the next was a number that acted as

an index

for procedural generation, and the remaining numbers and

letters set other parameters for the creation of

a unique cosmos.

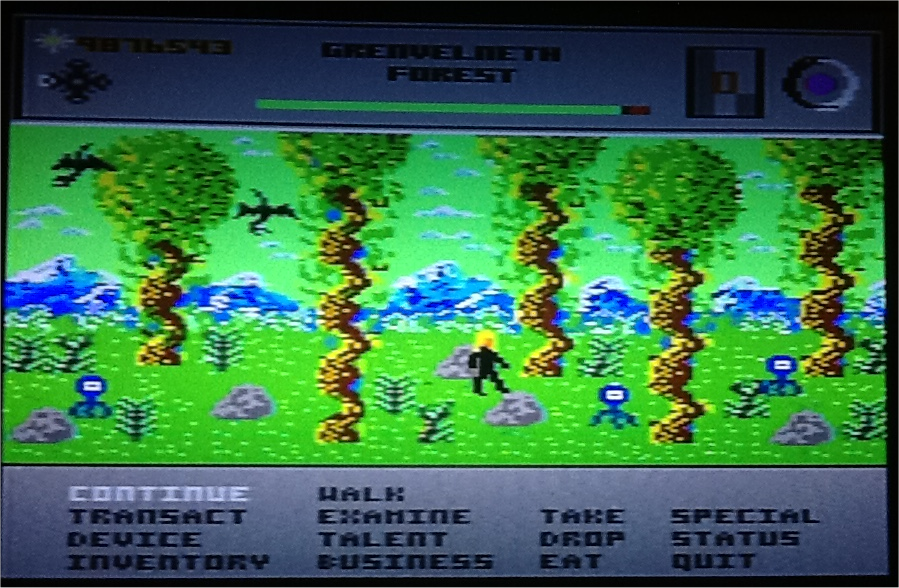

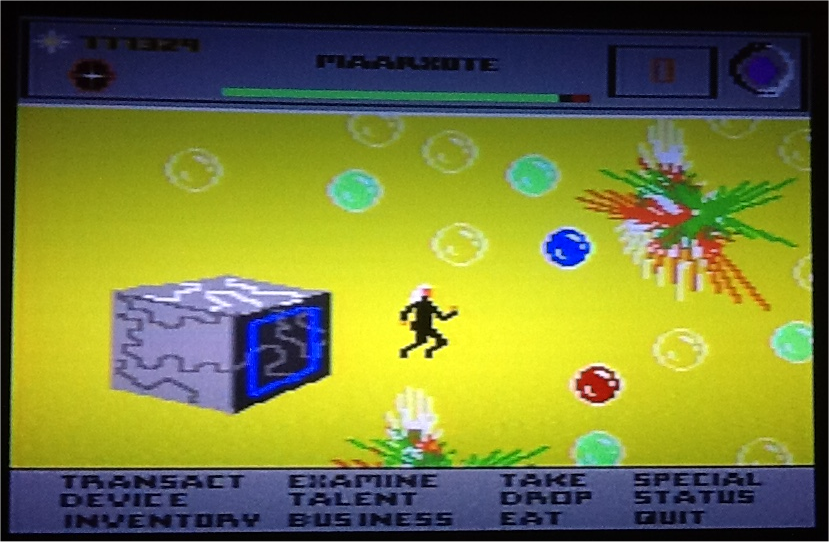

The player might end up anywhere. In this case, a forest on a planet with

a green sky. Small creatures would crawl or fly

or bounce around the

screen. Everything was procedurally generated - rules determined how to

combine creature, plant

or environmental components to 'print' a

final, finished sprite or background image to the screen. Creatures were

composed

of a top and a bottom, trees were painted using sections

printed to the screen for trunk or limbs or tops, even small plants

were generated using blocks of pixels printed over each other with

transparency. Background images were given simple

collision volumes

forcing the player to walk around them or jump over them or whatever. The

player had limited movement

within a region that made up the lower

third of the play window. The player sprite could only face left or right,

but it worked

very well even so.

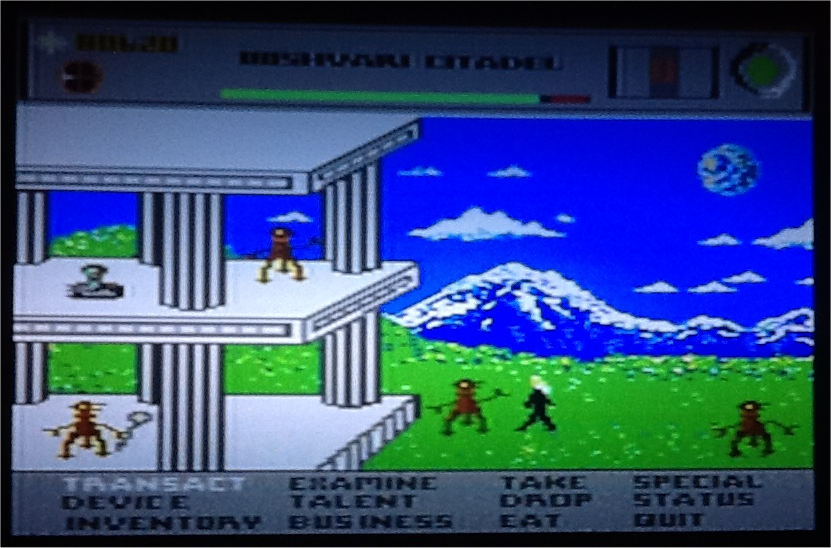

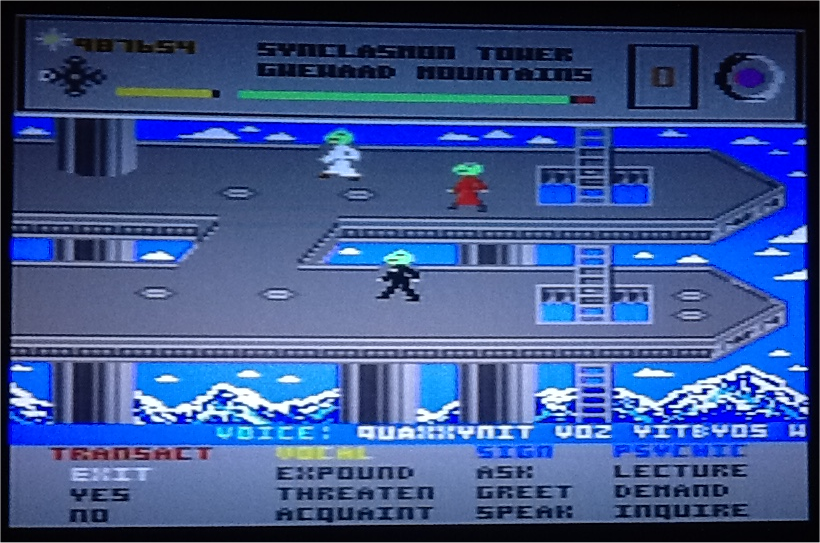

Aliens and alien buildings were generated according to rules. Aliens were

made the same way as the player,

a top and a bottom were combined to

make a finished sprite set. Pressing the menu button allowed selections to

be made.

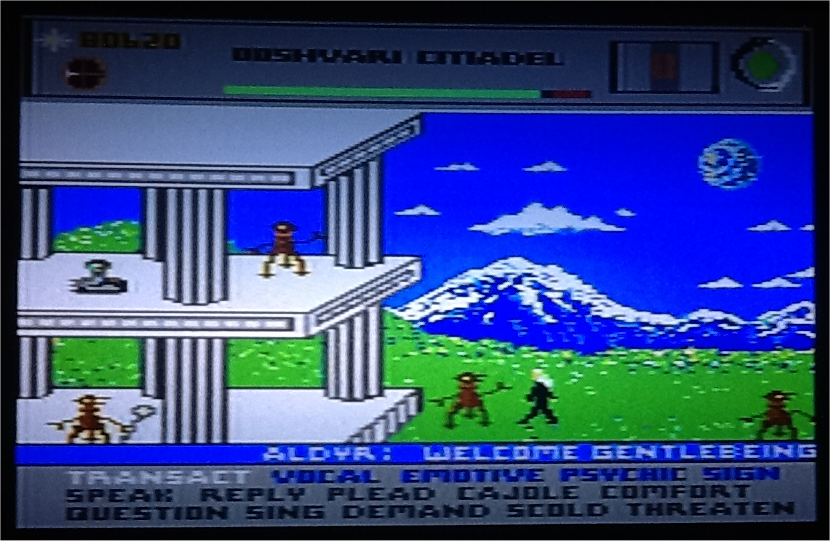

Communication happened in a scrolling strip at the bottom. The player

would not necessarily know the language

of the aliens in the game, and

in that case would see generated fake-language words. The use of

translator devices

in one's inventory - rather like Star Trek - changed

the scrolling words to readable english.

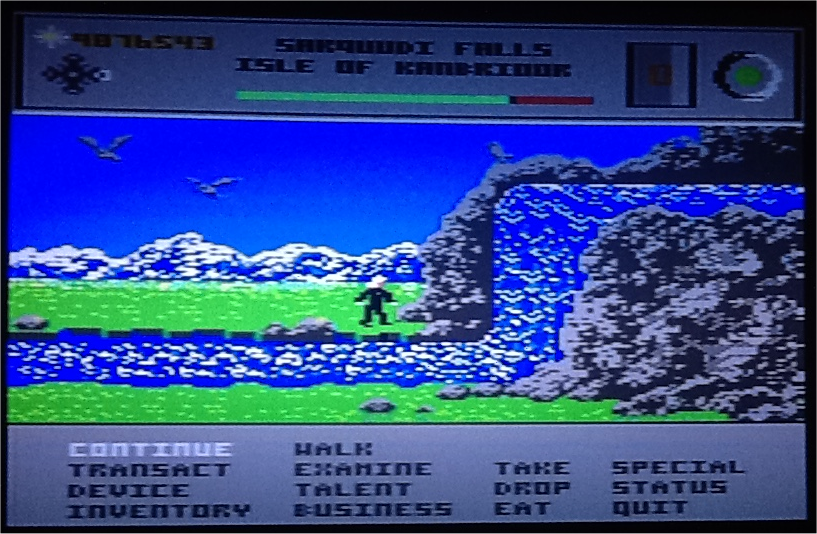

Because of the free movement within the play area of the screen, regions

with illusory 'height' were a trivial

matter to generate. The player

here might cross the river, and climb up the rocks, for instance, to reach

the

level above. Or, if they had a jet pack, or a talent like

levitation, they could fly through the region.

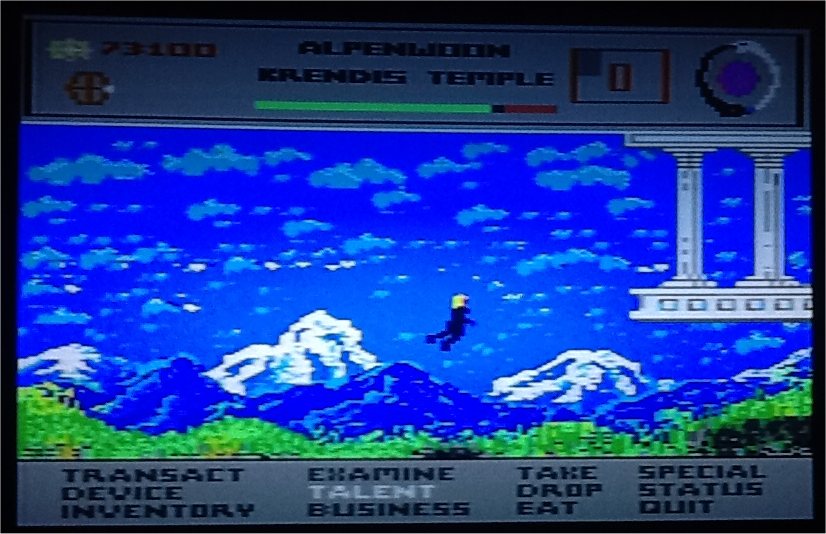

Talents were essentially psionic powers, they could be gained in various

ways. Talents included levitation (shown here),

or healing, or...

basically spells.

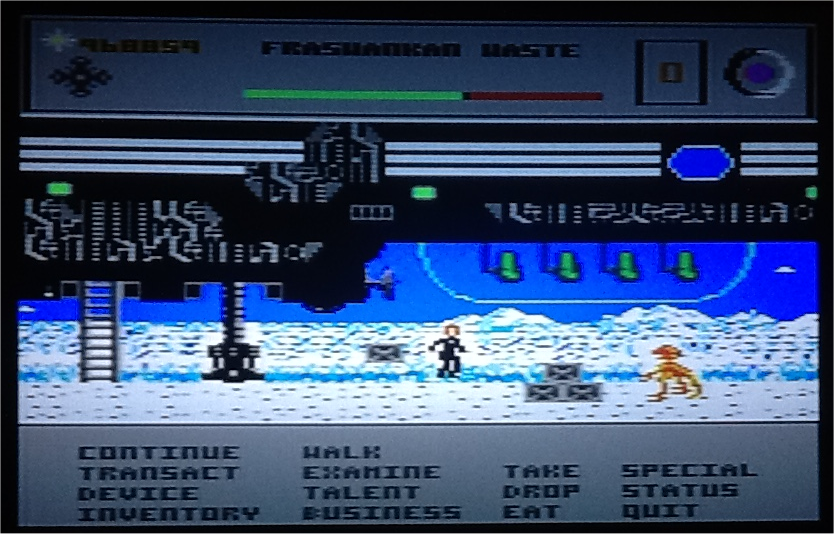

Here is an example of a language that the player does not know, and has no

translator for. Also note that

a player need not be human - this is a

lizard-person version of the base character shown.

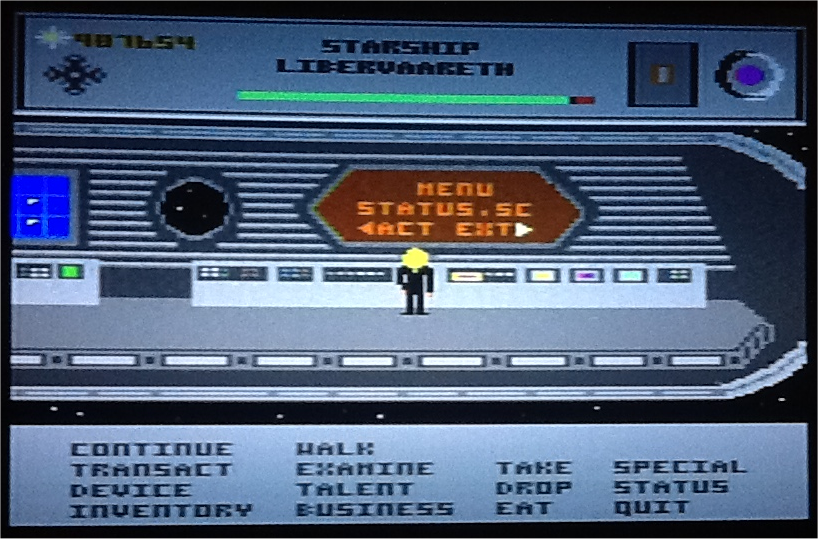

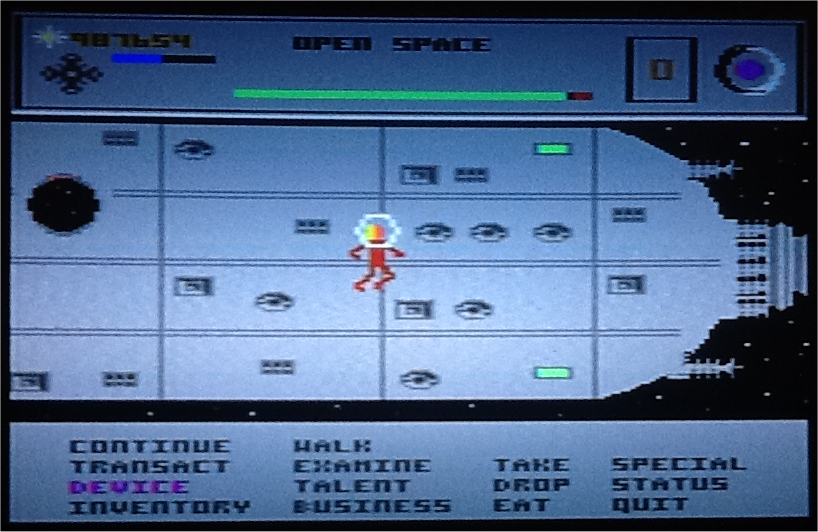

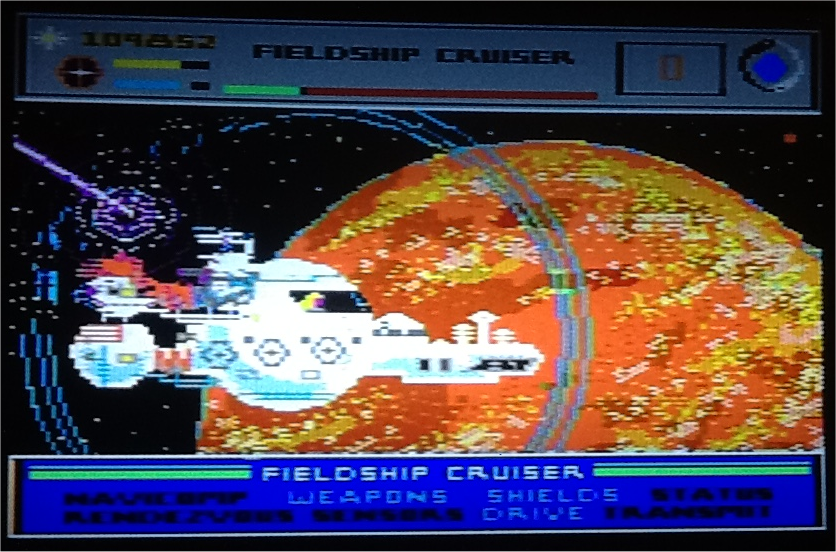

Owning a large star ship was possible, and this is a view inside just such

a ship. Standing in front of the

console allowed access to various ship

menu options, presented on the 'screen'.

You could exit the ship, in space, and do an EVA. Since a starship is

basically just a type of building, the same

mechanism is in place,

outside the fascade of the ship appears, hiding the interior, thus making

it look like the

player is truly 'outside'.

The player could then float around and see their ship from the outside...

or go visit an asteroid or other

object in space. Essentially the same

code used for the inside of the Multiversal Mover - a freescrolling

region the player could move around in.

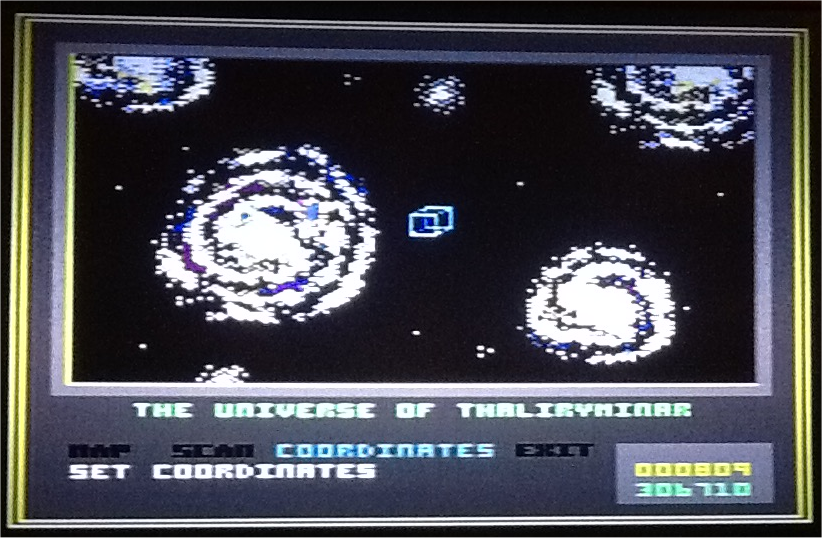

Every universe had a name, and a map. This is the map of just one of

countless universes. Everything was generated

by indexing a 10K block

of random numbers, which told the program where to paste and print every

image, or how to

generate any name or word or any other part of the

game, using rules. This universe is like our own - galaxies and space. But

there were universes where this map would look like floating triangles or

ribbons of land hanging in a colorful void.

There were eight different

- very different - available universe types.

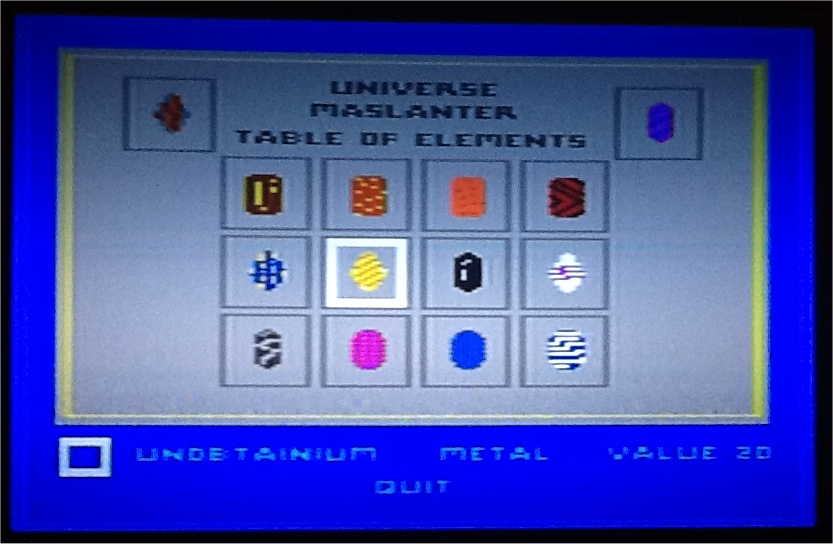

Every universe had it's own, unique periodic table of elements. The

fantasy elements could be found on

planets, or on asteroids, they could

be traded for 'Til' a form of universal currency. Different elements were

more or less valuble, and more or less rare.

Here is a map of an earthlike planet. The map scrolled in the window. The

maps were divided into a grid of

lines, each line passed over the

pixels of the map. The pixel colors determined what a given region would

contain

once entered. Green was grasslands, white was mountains with

snow, blue was water, dark green was forest.

A region - a side

scrolling 'level' - could contain multiple types of environment. Every

region had a start and an end.

The start and end were points on the

map, above. To cross a planet meant selecting regions and traversing them.

I got the idea from Activision's 'Pastfinder'.

The same map, scrolled a little to show how that works.

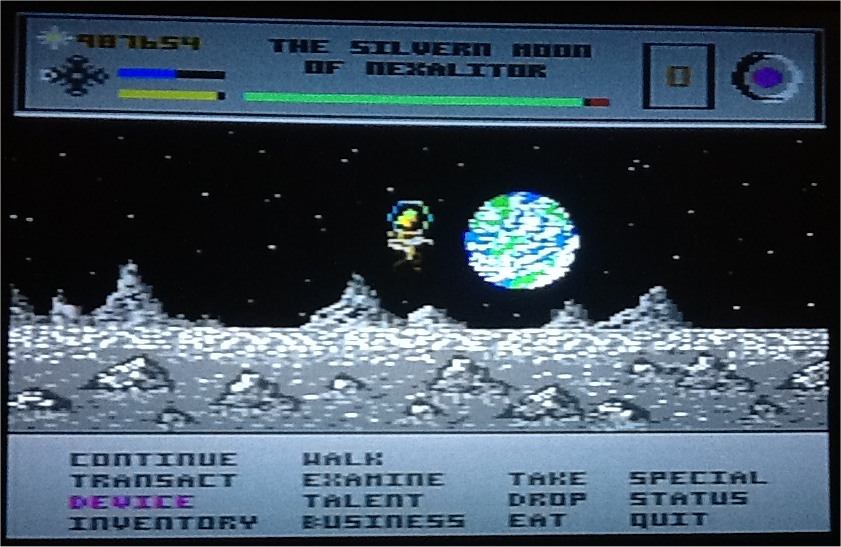

One could land on a moon, here is the player with a helmet and a raygun bouncing in low gravity.

A space ship makes a landing on a planet with... balloon trees or

something. Procedural generation is always

filled with stuff you cannot

predict.

Same ship, different planet. In this case, the player is involved in a cargo dispute with a weird creature.

Space battles were possible. Here is a small ship being hit and damaged.

These scenes played out

like movies, they were not joystick-play.

Space combat was tactical, not real-time. You made moves on a grid, and the results were shown as above.

Some ships, capitol ships, could be quite large. Since they could not land, they used...

Teleporter beams. Hey - I really liked Blake's Seven and Star Trek.

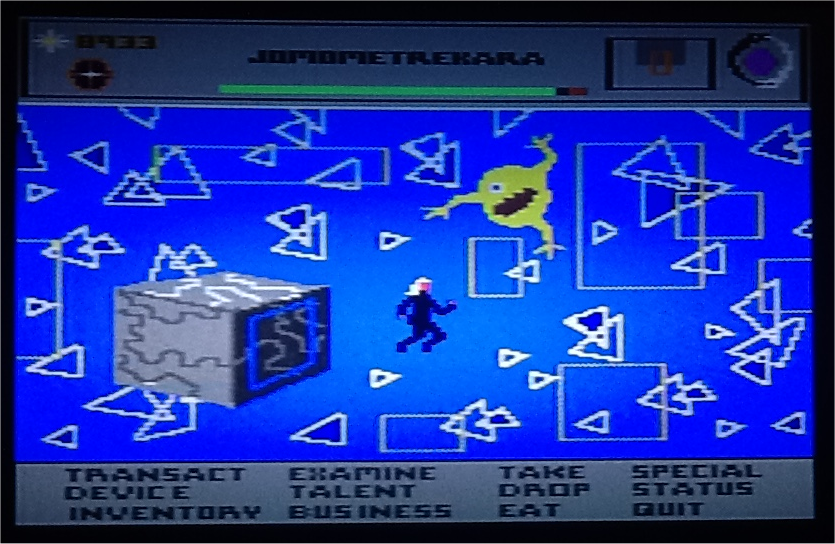

Flatland - Edwin Abbott's Flatland, sort of, was one of the possible eight universe variants.

Another was this chaotic cosmos of floating planes and weird creatures.

There were no planets as

we understand the concept here.

I actually had a dream about this particular weird, gravity-less universe.

In the game, those KIX-like objects

served as the local 'trees' for

lack of a better term. The people were orbs.

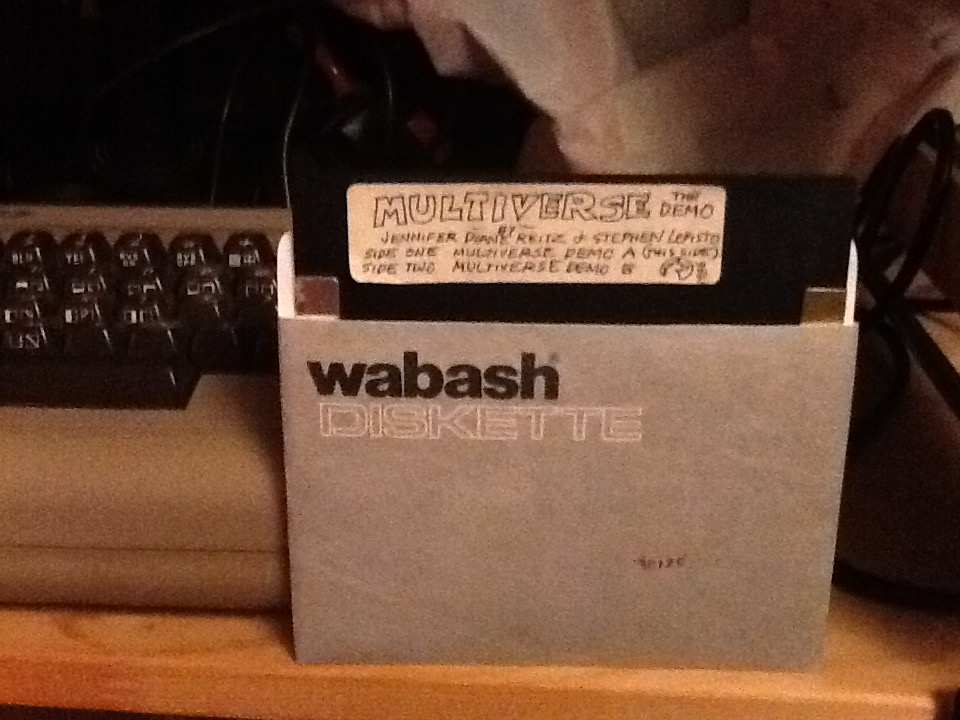

This is the disk. It is very old and it doesn't run very well anymore. It was a pain trying to get these images.

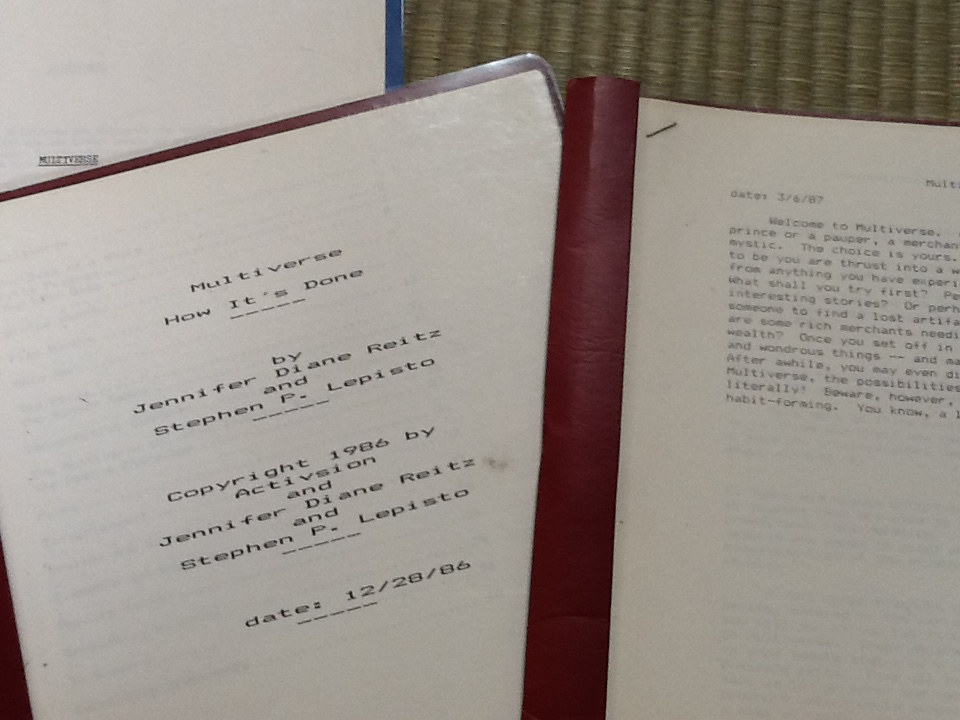

These were the documents I used to get the project greenlighted at

Activision. My producer was Brenda Laurel. She

really fought hard for

me, but I never got to see my game finished or released.

You have to go into a lot of detail to get a game sold. I walked away the

same day I went in with a 10K check. I was

so proud at the time. After

Activision folded and was sued, I got all my rights back. Not that it

matters in the least. I also

got a pitiful class-action check too.

Activision came back, a year later. The whole venture was just a mess.